My note taking setup

January 3, 2021

2020 was generally an unproductive year for me. Like a lot of people I spent far too much time doom-scrolling through Twitter and Youtube, and constantly checking the news. While most of the content I consumed was noise that I could’ve done well without, I did fall into a few rabbit holes here and there that eventually did improve my quality of life. And probably the biggest one out of them was discovering the (rather niche) category of non-linear note-taking apps.

In regular hierarchial note-taking apps like Notion or Evernote your notes are organised in a tree-like structure. For example, they are organised starting from the top-most area, to the subject, to the topic, and then finally to the note. While this form of linear note-taking works well for some type of notes, it can be very rigid for areas like research where the boundaries aren’t well defined (and for good reason). Such a setup can also introduce a lot of friction as you need to carefully decide about which ‘note book’ a particular note needs to go into. Non-linear note-taking apps turn this structure on its head by giving you a blank slate to start with. You take ‘daily notes’ and as your notes accumulate, you reference your old notes and form links between them which results in a ‘knowledge graph’. This actively encourages interest topics to be formed bottom-up and connections to be formed between different areas. There has been an explosion of such apps in the last couple of years, which I think can be traced back to this great talk by education researcher Sönke Ahrens in a developer conference where he first advocated for the need of such apps (and his book). I invested some time playing around with Roam Research, Obsidian, and Dynalist before finally converging to Remnote.

The great thing about Remnote is its tight integration with active recall and spaced repetition. Active recall and spaced repetition, as you probably already know intuitively if not the names, is the practice of actively testing yourself on topics and trying to retrieve them from memory in increasingly-spaced intervals of time. This is a far more effective strategy to understand and learn new topics, and also retain them, than passively re-reading them. Remnote implements this by automatically converting your notes into flashcards that goes into a daily practice queue. Based on how well you answer a card, the app decides when to show you the card the next time. This is similar to the Anki app, but unlike in Anki your cards are not disparate objects but instead belong to your notes which in turn belong to your knowledge graph.

While flashcards are generally used to remember raw facts or cram for exams, I think they have a much bigger scope. If used properly, they can help with retaining fundamental concepts and forming a strong base, understanding new topics deeply, and re-discovering old ideas and sparking new connections. I currently use Remnote to mostly make notes and flascards about the research papers or textbooks I’m reading, and some code API which I might need to use again. I also sometimes use it to make flaschards about quotes and ideas from any non-fiction book that I’m reading, or even some interesting works of fiction that I want to be reminded about again. I generally go through my practice queue on Remnote once or twice during the in-between moments of any day such as when I’m eating or walking.

Continued on July 4th, 2021

I will now try to explain how in more detail about how I organise my notes inside Remnote. While I use Remnote to hold notes from all aspects of my life, I will restrict myself to research notes in this post. This includes notes from papers and textbooks I read, lectures, projects, and my to-do tasks. I follow the Zettelkasten system to organise all my research notes and ideas, adapted from Sönke Ahrens’ excellent book linked above.

There are three main types of notes in the Zettelkasten system: permanent notes, literature notes, and reference notes. Reference notes is a collection of all research papers of interest. Literatures notes are notes made while reading papers and other material. Permanent notes is the main set of notes for collecting and generating ideas. An important feature of the Zettelkasten system is that it is not meant to simply be an archive of notes, rather it is meant to be a system of inter-connected notes to think with. Now allow me to explain this further with examples.

Reference notes

This is a simple page where I merely ‘dump’ all papers of potential interest as and when I encounter them. Here I copy-paste the title of the paper along with a link to its PDF. I also tag each paper according to areas or topics that already exist in my permanent notes to allow quick filtering. More importantly, by adding the tag the reference gets connected to my living set of permanent notes where I am likely to revisit it again.

Though this is the simplest step in the process, it is also currently the step with the most friction in my setup. This is because I often encounter papers that don’t have free web access links, and even with the link it takes me many clicks before I can finally open the paper on my favorite iPad app for reading (LiquidText). This process was seamless when I used to use Paperpile, but Paperpile was disconnected from the rest of the Zettelkasten. The paid Remnote Pro however has the ability to upload papers directly and is something I’m seriously considering.

Literature notes

These are notes made about the content of each paper I read. For a lot of papers, I only read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, and based on this I write at least one paragraph about the high-level idea proposed in the paper and what makes it different from other work. If the paper is of interest and I read further, then I usually tend to make more detailed notes about the described formulation including any equations, types of experiments and their inference, motivations. Importantly, I try to write all this in my own words and do not copy-paste to help my own understanding. I also make similar notes for textbooks, lectures and talks, but often they are already very structured so I tend to add them directly to my set of permanent notes.

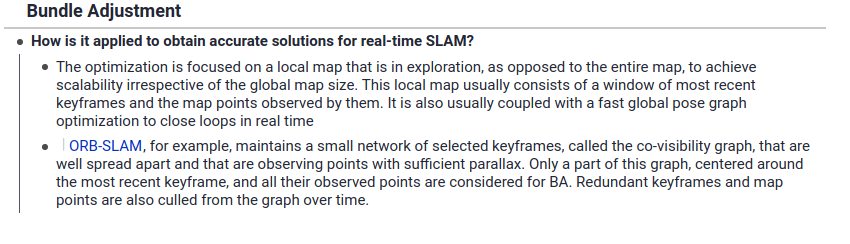

Permanent notes

This is the main knowledge base that consists of precise and self-contained notes clustered into topics, questions, and projects. This is also a thinking space where topics, questions, and ideas are developed bottom up from the exiting notes. I add new notes by building on my literature notes and from what I read, thinking about how they relate to my own topics, research and interests as found in my existing permanent notes. I see what is missing, what questions arise, how notes can be strengthened or challenged according to the new information. As a concrete example, the following is a permanent note I developed about bundle adjustment where I’ve written about how it is adapted for real-time SLAM. I’ve developed the argument further by linking a literature note I made about ORB-SLAM.

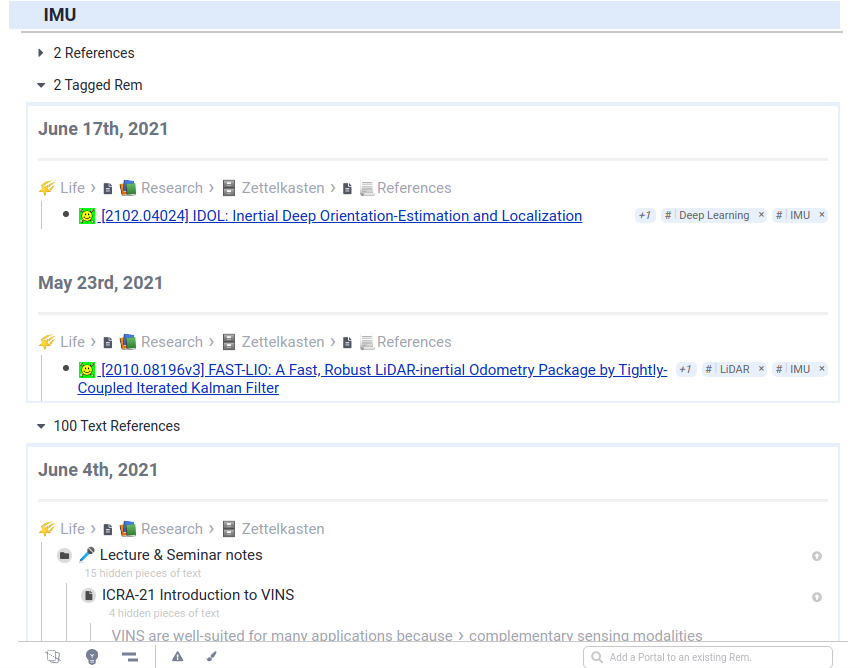

Remnote acitvely helps build these connections by also showing within the same note all the places where the same topic has been mentioned or referred to. For example, the following is a permanent note about IMUs where Remnote lists and auto-populates all the references to it.

By actively thinking about and linking what I read to this permanent set of notes, the knowledge base is strengthened and new arguments and ideas are developed. If any new promising insights or questions are developed that are project-worthy, I move them to a separate note called forschungsfragen, which means research questions, where I build on them further over time (the name is a cheeky reference to the novel All the Light We Cannot See). This way you also get to start working on projects and ideas from what you already have and don’t have to start with a clean slate each time.

Flashcards

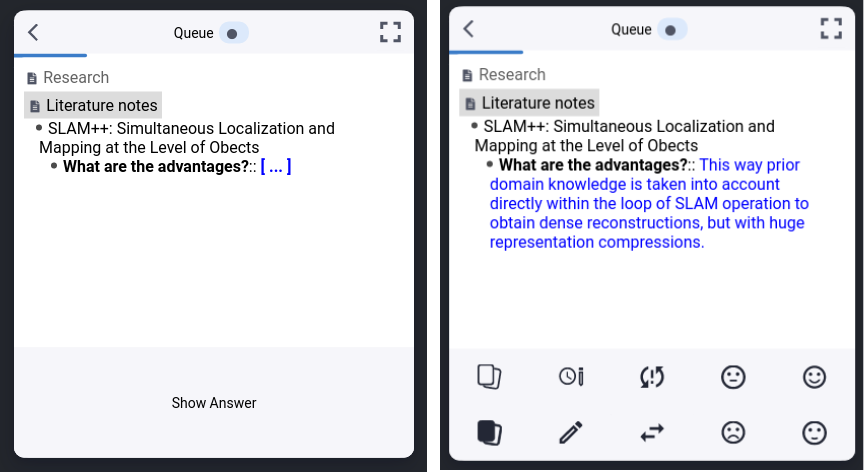

In addition to bi-directional linking, the one other feature of Remnote that I use heavily within my Zettelkasten setup is flashcards. While preparing notes in my own words and actively connecting them to exiting notes helps with understanding, durable learning requires active retrieval practice. By preparing flashcards from my notes, this retrieval process becomes an active choice than something that is left to chance encounters. Remnote makes the process of preparing flashcards very simple. I just have to add a question?:: phrase before each note and it automatically gets converted to a flashcard and added to my practice queue. I make these flashcards both from my permanent notes and literature notes. By having a global queue that accumulates flashcards from across the system, Remnote also encourages retrieval practice in different contexts, actively encouraging new connections and insights.

Conclusion

Other than these types of notes, I also maintain to-do lists for tasks, papers and topics to read about, and daily work logs. My daily work logs are mostly project-related where I write down what experiments were tried out or thought about, which I then review weekly to plan the next steps.

This concludes my research notes setup. Any setup is only as effective as our ability to use it. Though the Zettelkasten setup is simple in theory, if you don’t actively read with an eye towards building existing notes and connections, it can quickly become an archive of sorts where you just take out what you put in, and not an external system to think with. The purpose of any note taking setup is to not just serve as a storage of information but to serve as an external scaffolding for thinking.

Though the system hasn’t helped me yet with generating any new promising research ideas that I’m working on currently, I do believe in its potential over time. But it has certainly helped with my understanding and in organising my thoughts. It has also helped improve my writing - for my most recent research paper I was able to quickly write a first draft by moving notes from my permanent notes. Practicing flashcards has been immensely helpful for me in solidifying my knowledge. I also find the practice to be very meditative and enjoyable. So much that it’s now an active part of my work routine - I actively answer a few flashcards to help calm my mind and ‘get into the zone’ just before beginning my work session. I also found it useful while preparing interviews, helping me to actively test my existing knowledge and fill up holes. If not the Zettelkasten, I sincerely hope that you atleast try out incorporating flashcards into your workflow.

I hope you found this post useful and that it helps with building your own research notes setup. Feel free to email me to share your opinions and workflows!

Further reading

• How to take smart notes - Sönke Ahrens (Highly recommended if you have the time, this book talks about much more than just how to take notes)